This story was written by Jill Rosen and originally appeared in The Hub.

Click here to read a story about the findings in this study in The Guardian, which was written by Fiona Harvey.

With deadlines to address climate change looming, countries worldwide missed a chance with unprecedented pandemic stimulus spending, a new Johns Hopkins University study finds.

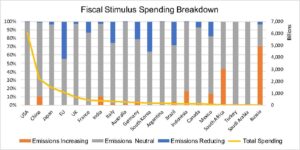

Analyzing over $13 trillion in COVID-19-related stimulus packages from 19 countries and the European Union, just 6% of the money went to projects that will likely reduce greenhouse gasses, while the vast majority of recovery spending didn’t address climate at all. Another 3% of stimulus spending went to projects likely to increase emissions.

Analyzing over $13 trillion in COVID-19-related stimulus packages from 19 countries and the European Union, just 6% of the money went to projects that will likely reduce greenhouse gasses, while the vast majority of recovery spending didn’t address climate at all. Another 3% of stimulus spending went to projects likely to increase emissions.

The findings are published today by Nature. Lead author on the paper was Jonas Nahm, an assistant professor of energy, resources, and environment at Johns Hopkins’ School of Advanced International Studies who is also an affiliated researcher with the Ralph O’Connor Sustainable Energy Institute (ROSEI). Another author was Johannes Urpelainen, the Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz Professor of Energy, Resources and Environment at Johns Hopkins, who is also a member of ROSEI’s leadership council.

“These economic recovery packages provided an opportunity for countries including the United States to really envision what they want their economies to look like going forward,” said co-author Scot Miller, an assistant professor of environmental health and engineering at Johns Hopkins. “The pandemic could have been an opportunity to push countries toward greener economies and a lot of governments have failed to do so.”

Governments typically prioritize economic growth over climate protection, particularly during economic downturns. Yet stimulus spending during recessions offers an opportunity to combine climate and economic objectives, the authors say. In the aftermath of the 2009 recession, for instance, 16% of global stimulus spending targeted emissions-reducing activities.

The team analyzed each nation’s stimulus policy from the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 well into 2021, considering the percent dedicated for activities that would increase emissions, lower emissions or that were emissions neutral.

Of the $13 trillion nations pledged for recovery efforts, just 6% targeted activities that would reduce emissions —investments in electric vehicles, transit infrastructure, energy efficient homes and offices, and renewable energy research. Countries spent less $1 trillion on projects that would cut greenhouse emissions, either directly or indirectly.

“Even though this was a public health crisis, in principle governments could have intervened in the economy in a way that changed everything, getting together to do something really big to meet the climate challenge,” said Nahm. “But the vast majority of the money spent has very tenuous relations to emissions so it was, overall, very disappointing.”

The team found that of green stimulus measures, only about 27% would directly reduce greenhouse emissions. The remaining approximately 72% would have an indirect impact at best, projects like subsidies for biofuel producers in Brazil, or funding in Germany to aid the construction of electric vehicle charging stations.

Countries that dedicated the most stimulus money for green projects include South Korea and the European Union, each dedicating more than 30% of their packages to such measures. Brazil, Germany and Italy invested more than 20% of their recovery spending in green projects while France spent just over 10%.

Countries that barely considered climate-related projects in their recovery plans, spending less than 5% of their totals, include the United States, Japan, Russia, and the United Kingdom.

The trillions of dollars spent globally, mainly on unconditional checks for individuals and businesses, could have covered the necessary investments in technology, infrastructure, and research and development to meet the Paris Agreement climate goals, all while creating jobs and economic recovery, the authors said. As part of this agreement, many countries have set interim emissions goals for year 2030.

“If there was ever an opportunity to tie economic recovery with these climate goals that are drawing closer by the day, this would have been the time to do it,” Miller said. “In the months and years ahead, we shouldn’t forget about climate and greenhouse gas emissions goals when devising economic recovery measures. These 2030 climate goals are coming faster and sooner than we think and we can’t put off thinking about climate change until the pandemic is over.”